In which I look more closely at one particular, well-known data set: what makes it what it is, and what we might draw from the way it’s managed to help us with some other challenging questions about privacy and transparency.

Surely data is open, or it isn’t?

(I’m using “open” here as shorthand for the ability to be reached and reused, not with any particular commercial or licensing gloss. It’s a loaded term. But let’s not snag on it at the beginning, hey?)

Data is either out there, on the internet, without encryption or paywall, or it isn’t. And if it is, then that’s that. Anyone can reach it, rearrange it or republish it, restrained or hampered only by such man-made contrivances as copyright and data protection laws.

Maybe. Maybe not.

I’ve been involved in some interesting discussions recently about the tricky issues surrounding the publication of personal data. By that, I mean data which identifies individuals. To be specific: some of the information in the criminal justice sector about court hearings, convictions and the like.

You’ll have seen much in the press, especially following the riots, about a renewed political and societal interest in this type of publication.

Without making this post all about the detailed nuances of those questions, this broader issue about the implications of “open” publication seems to me to need a bit more exploration before we can sensibly make judgements about such cases.

And to do that I took a close look at one very well-known data set: the electoral register.

What is it? Well, it’s a register of those who’ve expressed their entitlement, being over 18 (or about to be) and otherwise eligible, to vote in local and national elections, through returning a form sent to them by their council each year. If you’re reading this, you’re probably on it. I am.

It’s therefore not: a complete list of people in the UK (or even of those entitled to vote); a citizenship register; a census; a single, master database of everyone; accurate; or a distillation of lots of big government systems holding personal information.

What’s it for? An interesting question. I suppose its primary existence is to support the validation of those entitled to vote, at and around election time. But you’ll know, if you have voted, that it’s more of an afterthought to the actual process; most people show up with polling cards in hand, and anyway, there’d be no possibility of any real form of authentication, as the register doesn’t contain signatures, photos, privileged information or any other usable method of assurance. It’s not even concealed from view. (More on that here.)

But it does some other things, doesn’t it? It provides a means for political candidates to be able to make contact for canvassing purposes with their electorate. And I suppose, for that reason, it has this interesting status as a “public document”. Which we’ll come back to in a moment.

And to complete the picture, a subset of it (the “edited register”) is also sold to commercial organisations for marketing purposes, enabling them, amongst other things, to compile pretty comprehensive databases of people.

…and as a byproduct of that it also forms an important part of credit-checking processes–with said commercial organisations able to offer services, at a price, to anyone who wants to run a check that at least someone claiming to have X name has at some point claimed to live at Y address. (Remember, it’s all pretty weak information really, self-asserted with no comprehensive checking process.) You can opt out of the edited register if you choose, but you’re included by default.

[Update 2 Oct: Matthew, below, comments that I’m not quite right here–the full register is also available to be used for credit checking]

There’s probably more, but let’s get stuck into some of this.

First off, I will happily add that the whole business of why it needs to be public at all seems highly questionable. And I don’t remember the public debate where we all thought that it was a great idea to try and make a few quid off the back of this potentially highly-sensitive data? Do you? How do you feel about that?

And the idea that the process of democracy would be terminally hampered were candidates, agents and parties not able to make checklists of who’d been canvassed? Really? Couldn’t they perhaps just knock on doors anyway? As a potential representative would I only be willing to learn from encountering those who had a vote? I suggest not.

So, moving on past those knotty questions about “why do we have it, and why do we sell it?”, we have in practice established some conventions about managing it as “a public document”.

Can I, as a member of the public, request a copy be sent to me? Certainly not. Ok, perhaps I can download it then? Nope. Search it online? Hell no.

I can go and see it in my local library.

So I did.

I heartily recommend you do the same. It is a real eye-opener in terms of the idea of data being “semi-public”.

I trotted up to the (soon-to-be-closed [boo hiss]) information desk at the library under Westminster City Hall.

–Can I see the electoral register please?

–Sure. We only have the edited version here: if you want the whole thing, you have to go through there and ask for Electoral Services.

(He pointed at a forbidding and not-at-all-public-looking door).

–You’re ok, I’ll just have a look at this one

And out from the back window-ledge comes a battered green lever-arch file, containing bundles of papers.

–You know how to use this? he says

I shake my head. It seems the top bundle of papers is a street index. The personal information (names grouped by cohabitation, basically) is listed by street, then house name/number within street. Not by names.

So, you can’t, easily, find someone you’re stalking. (Did I say that? I mean, “whose democratic participative standing you have a legitimate interest in establishing.”)

But you can if you’re patient. Or if their name, like that of one Mr Portillo, leaps off the page at you. I intentionally chose the register of the area immediately around the Houses of Parliament, for just this reason. Curiously, I couldn’t actually find the HoP itself listed, but Buckingham Palace does have over 50 registered voters (none of whom are called Windsor.)

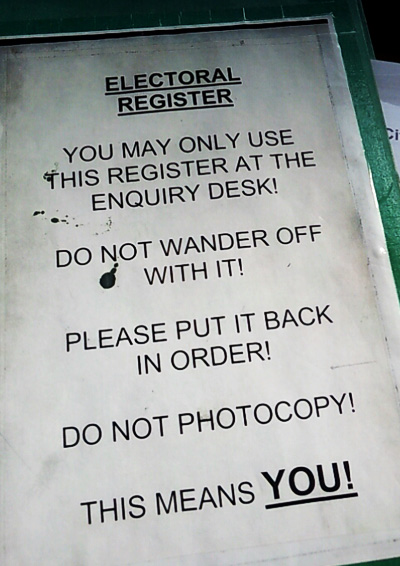

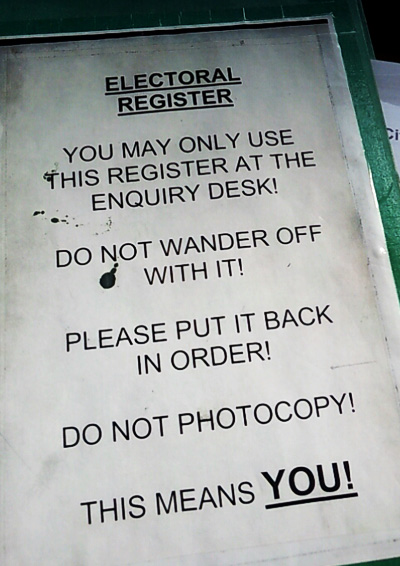

But back to the process: as I picked up the box to head towards an empty desk a finger came down on the lid: –you have to read it here, he says.

I look at the lid. Wow.

I ask the question about photocopying anyway, just to judge the reaction. Kitten-killer, his eyes say.

But I take it a few paces away anyway and have a closer look.

Fascinating. I see a bunch of well-known people from industry and politics, their home addresses, and who else lives with them.

I’m sure I’ll go grey in chokey if I actually published unredacted screen shots in this post, but I’m pretty sure this one will be ok; if nothing else I think its historical interest justifies it… (RIP, Brian.)

Now, in all the fuss we make about child benefit claimant data being mislaid via CD, and in all the howling we make about anonymisation of health records and other sensitive data, and through all the fog that surrounds the commercialisation of public information and the Public Data Corporation etc. isn’t this sort of information that we would normally expect to be the subject of an enormous public debate about even its very existence? And I’m walking off the street and making notes of it, and, and…

And I can see what’s happening here.

Yes, it’s “public”. Sort of. But so much friction has been thrown in the way of the process–from the shirty look as I have the temerity to request it, to the deliberate choice over structure that minimises me being able to quickly find my target–that I would strongly argue it to be “semi-public” rather than public.

There are some important lessons here perhaps when considering the mode, and the consequence, of publishing data online. Clearly, structure is highly relevant. If I am able to sort, and index it, that instantly creates a whole universe of permanent, additional consequences. Not all of which may be that desirable. “A perpetual, searchable, SEO-friendly database of all those ever summoned to court, convicted or not, you say? Certainly sir…coming right up.”

If I’m able to relate information–by association with others–I can also help the cause of those wishing to track someone or something down. Look at Facebook. It does a great job of finding people you search for, even those with very common names amongst its hundreds of millions of accounts, by this type of associative referencing. Powerful stuff.

And let’s not forget that ALL this information is pretty easily available online anyway. You just have to pay for it. The best-known provider that I’ve looked at, 192.com, has an interesting model. You’ll be giving them at least a tenner, and more like £30 to buy some credits to search their databases. And they have the ominous rider that their really sexy information–the historic registers, is only available at an entry-level price of £150 a year. For that reason, I haven’t actually given them a penny as yet. But it’s no obstacle to the serious stalker. I mean, researcher.

I’m sure there are all sorts of impediments, from download limits to penalties for misuse, that attempt to put further spokes in the wheel of it becoming a common commodity. But how long, really, before the whole register is available as a torrent on the Pirate Bay? Maybe it is already?

And we’re not bothered about this? It’s amazing, isn’t it? Yes, this whole industry is built on data that we’re required to submit to public authorities–and if we don’t, we’re disenfranchised.

This is a scandal, and one that urgently needs review.

But do take away the point that there is such a concept as “semi-public” – at least for now. It’s the ability to process, to restructure, to index, that makes online data different from those box files in the library.

The friction we throw into the system, whether it’s (intentionally?) releasing information via pdf, or slipping a local journalist a hand-written note of the names of those in court, is perhaps more than just dumb intransigence in the face of “information that wants to be free”. And it can serve some potentially legitimate social purposes.

Think how you’d feel if those frictions weren’t there around the electoral roll? Even the money that 192.com require for you to buy back the data you gave up in the first place?

Happy that every comment you made online under your own name, every mention in the press, could be traced back to your real address along with the names of your (18+) family? I think perhaps not.

So, a very big public debate is required on the consequences of any personal data being put online. But remember, stealthily or not, we’ve had experience of these issues for years. We just need to look on the library window-ledges to find it.