Mar 14, 2011 12

Broken journey

I’ve seen an awful lot of online government, of one form or another. Consultations, information, tools, maps, communities…and transactions. Transactions really are the very bugger to get right, aren’t they? You wouldn’t think it was that hard to do the basic capture and interchange of information, would you? That there could be so many places to trip up: from daft processes, to forms-turned-into-websites, to mismatched authentication in relation to actual risk, to dreadful, dreadful interaction design.

But there are. And today’s was a gem. Not so much for what it showed about the actual online transaction (which had its issues). But for staggering failures of design around that little thing called a “customer journey”.

It may be a bit of jargon, but the “journey” concept is important. And it’s not just the bit from “land on the right webpage” to “transaction completed”. It’s way broader than that. Or it should be. From the first awareness that something has to be done (or even including general awareness before that point) right the way through the transaction, and on beyond the point of confirmation and into the territory of follow-up action and support. The whole thing. Across all the channels that might play a part (de-jargoning: channels are the types of communication that people can use: typically web, post, telephone, face-to-face and through an intermediary).

So let’s look at how badly this one failed.

A form landed through the post a couple of weeks ago. I need to update the photo on my driving licence. Fair enough. What’s in my wallet has diverged from reality a fair bit in nearly ten years (and I used a five-year-old passport pic even back then).

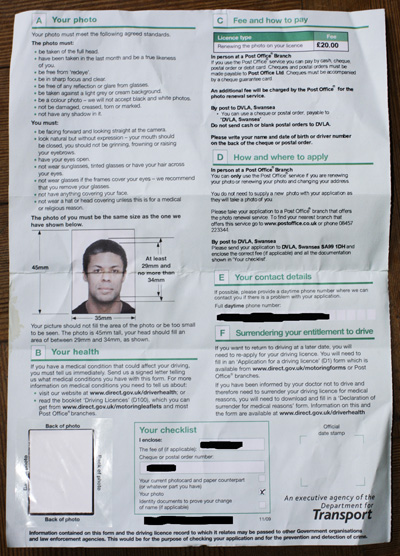

The form was interesting: I had a couple of options to update the photo. In person in a post office (where they’d even be able to take my picture for me), or by post. There was a covering letter on the form that even went to the trouble of telling me where my two nearest post offices were that could do the photo service bit. Nice, I thought. Very nice. A personalised touch on a standard form. Liking this.

But I griped when I read more closely. The photo replacement would cost £20. Fair enough, I supposed there’s some admin involved, and £2 a year doesn’t seem outrageous (though I guess a fair few people would find £20 hard to find out of the blue). And that photo service at the post office? Well, that would cost something too. But it was just left as “An additional fee…”–weird, I thought. Why not just print the amount? Was it £5, or £50? How was I supposed to make a sensible decision about posting or post-officing without knowing the facts? The £20 fee was printed: how very strange just to leave the other one to be a surprise when arriving at the counter?

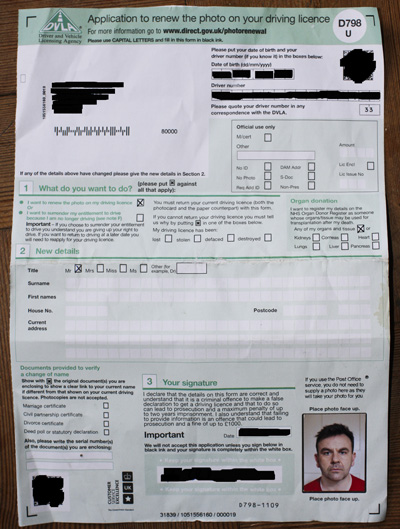

Another little glitch: the form (see pictures) suggests you go online, or pick up the phone, to find out the nearest branch offering the service, yet the covering letter that’s physically attached to the form tells you the two nearest, as I said. Little discontinuities like that are part of the customer journey. They’re causing me to read again, to look between the two documents at the discrepancy, to wonder if I’ve misread something. To make a phone call–a contact that could otherwise be avoided. Details, details, all very important.

The pictures are scruffy because the form stayed in my bag for two weeks, as I never quite found time during the day to go into a post office (and I was still unsighted on how much I’d actually have to pay). As I take photos, I decided today to just shoot one to the required spec and get the damn thing done.

It’s a simple form. It asks for a few bits of information, as well as the photo (which it says must be taken within the last month). Or does it? Please put your date of birth and driver number “if you know it” in the boxes below. (Don’t I just HATE that “if you know it”–it’s a little clue to a bit of poor design…)

Let’s think again about the journey. The way the form has to be used within a wider context. In other words: this form has to be sent back (according to section 1) either with both driving licence parts, or with a declaration that you don’t have them any more. In the first case, they’ve got your date of birth and driver number plastered all over them, so why ask for them again? In the second case, you’re not that likely to know your driver number, are you? And we’re absolutely certain that submission of date of birth is critical here for “security” purposes, or whatever? Really? So those information requests may as well disappear from the form, no?

And before leaping to the conclusion that they must be there as a failsafe in case the envelope’s contents are broken up and dispersed, remember that the form is preprinted with my name and address. Not that tricky to match up with all the stray pink cards lying around on the floor in the post-room in Swansea, now is it?

A couple more check-boxes, a section on organ donation, stick on the photo, and off we go.

Hang on–that organ donation bit: is that section compulsory? It doesn’t say. I can choose between giving my entire usable remains or a selection of organs. Will the form be rejected if I leave them all blank? Stuff like this will cause some forms to be thrust to one side rather than be further completed, perhaps permanently. Never, ever, leave room for doubt.

On the back there’s a whole load of A-F guidance notes. Nothing to fill in. Well, if you actually stop to read (how many will?) B is a quite important section on declaration of health conditions. But nothing to fill in, so I guess it just gets left. Somebody’s box has no doubt been ticked in Swansea. So that’s ok then. There’s some nudging towards Directgov to get further info (oh look, the journey now has an online component–that’s nice).

And so I think: I just spent a while doing a form to send a photo (which doesn’t have to be countersigned–I guess they have a visual inspection in Swansea to check I haven’t suddenly changed race, sex or grown horns) to an agency who are expecting it, and who know full well who I am. Why the hell isn’t this online? And I moaned and tweeted a bit. As I do.

And the shocking answer came back that there was an online service available. At Directgov. Oh, the irony: I worked there for a couple of years and thought I knew most of the available transactions in some detail.

This is the real journey failure. That the form has been sent through my door with no mention whatsoever of the online service. Wait, look back at the very top: that Directgov URL (no, I hadn’t seen it until this point). That starts me off towards an online transaction, though for some inexplicable reason it’s been coded as “For more information…”. Admittedly, it’s the usual “before you apply…” rigmarole (we have to just suck this up, apparently…) but it’s there!

Ah, wait, the handy …/photorenewal URL actually takes me to a whole bunch of other driving licence services (most of which have sod all to do with photo renewal) rather than this one which looks more like it. And yes, even here, I have to do another click to actually get me to the transaction. Because there’s some other information on the page: oh look–there’s the mystery post office service charge–£4.50. Why hide it away there?! And loads of stuff about how to go to a post office and do it…hang on, are we trying to promote the online channel or what? This is getting very confusing. I can now see I’d need a form D798 if I did. But MY form (check those pics) is a D798 U. Now that might be the same form. But it’s another bit of uncertainty. Details, details, again. Another reason to shove it in a drawer, or a bin.

Let me spell this out. Money has been spent creating an online service that (in theory at least) will save the public time, and the taxpayer money. And the people who send out the forms (which is how you know about the service) don’t even mention that it exists as an option. Has anybody actually tested this as a journey? (It was at this point of realisation that I went, as they say, a bit ape.)

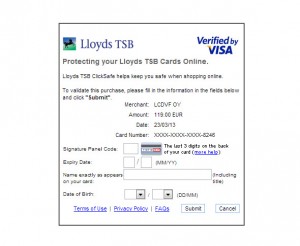

And then, the coup de grâce. I hit that “Apply Online” button. It tells me the prerequisites. I need a passport issued within the last five years. Ah, I get it now. If they can verify who I am (they ask for previous addresses, and presumably run an Experian or similar check; in combination with a presented passport number that will probably suffice) they will drag my passport photo between systems and bingo, my driving licence will have a new photo. Presumably there is relatively little risk doing it like this: it’s not as if I can slip an entirely bogus photo into the systems this way–which seems like the main fraud risk within this whole process. (I have skipped over the “role” of the Government Gateway for brevity. More on that can be found here. Though it does at least appear to offer me access to a DVLA dashboard of my information, including my old photo! Which is quite cool. Though what would happen if I connected a second Gateway relationship to my DVLA info is anybody’s guess…)

That’s a “new” photo as in “up to five years old” of course–or possibly even older…is it just me? Is this all sounding both wonderfully joined-up and strangely discontinuous all at the same time? The photo has to be no older than a month by post or post office, but up to five years is ok if you do it online. Riiiiight.

Sadly my passport is a fraction over five years old, so it’s game over online, for me anyway. And why can’t I just email them the damn photo or upload it on a website? There’s nothing on that paper form that I’d be unhappy putting in an email, or a web form. And the picture wouldn’t need rescanning. And I could just certify that I’d destroyed the old licences (the paper process doesn’t fall apart if I mark that as having happened on the form anyway, now does it?)…I could go on, but I won’t. This post is way too long already.

This is an absolute, prime, simple, transactional government-to-citizen interaction. It is the sort of thing that could be reformed NOW. Without an elaborate authentication framework. Without a new website. Without changing more than a few fields and lines on paper and web (or at most, adding a simple image upload process if we really wanted to gold-plate things). The fact that we don’t, or can’t, change it is lamentable. There are no excuses. Really, there aren’t.

POSTSCRIPT

You’ll see in the comments below that I proudly maintained that my application would stay in its envelope, completed and unposted, until such time as I saw fit to, or was compelled to, submit it.

That smug stance was all well and good until I found myself at the Hire Car counter in Venice airport a couple of weeks ago. With an expired driving licence. No car for me. Game over.

While driving licence expiry doesn’t mean much in day-to-day life, when you need to hire a car, it suddenly acquires a new and terrible significance.

I could swear that on the breeze over the lagoon, I could hear a distant voice whispering to me all the way from Swansea:

“Who’s the c*** now, boyo?”