How do you make something freely available so that anyone can use it, but also build sustainable businesses on top of it?

It’s an aspiration that drives Wikipedia, innumerable open web projects and, in recent years, the thrust of releasing UK government – and government-funded/subsidised – data for reuse.

It’s also a complicated balancing act in terms of basic economic theory: prices find their natural level, and if something’s available for free, there’s always going to be a tension in competing with it. If there’s no added value, there’s no sustainable business.

Of all the sectors where data has been opened up, it’s in transport that I think the most visible and tangible advances have been made.

Transport data has many lovely qualities about it – it’s highly structured in time and location; it has extreme real-time relevance; and it affects people.

I don’t doubt that concentrations of heavy metals in the soil affect people, but with the best will in the world, not in the same way – and not in a way that’s likely to affect what time they get up or which route they choose to get to work.

The web, and then the apps, revolutionised the way we consume travel information, but none of this could be possible without the underlying data.

So is the freeing up of data entirely without complications?

First, a small diversion into history.

Long ago when I tinkered with these things for a living, I was much taken with the power of the bottom-up service “Fix My Street” to allow people simply and quickly to report defects in their locality. A quick phone pic, an upload via an app, and the matter was routed to the relevant authority – putting the burden on them to receive, process, and respond – all the while knowing their response (or lack of it) would lie in public view.

My exam question at the time: should such a service be given oxygen through association with government’s “official” channels for doing stuff?

There were some curious arguments thrown at me at this point: “but we spent lots of money on our own sites – people should use them” [NOPE, NOT BUYING THAT]; “it will erode understanding of who actually provides services, and therefore local accountability at the ballot box becomes less clear” [ER, MAYBE A BIT? BUT SERIOUSLY?]; and “if you put information like that into public view, people will use it to find potholes, drive into them, and claim against the council” [*WTYRF?]

And yet, and yet. We are merely fallible humans, and if there’s a buck to be made… Which brings me, in a very roundabout way, to the Delay Repay Sniper.

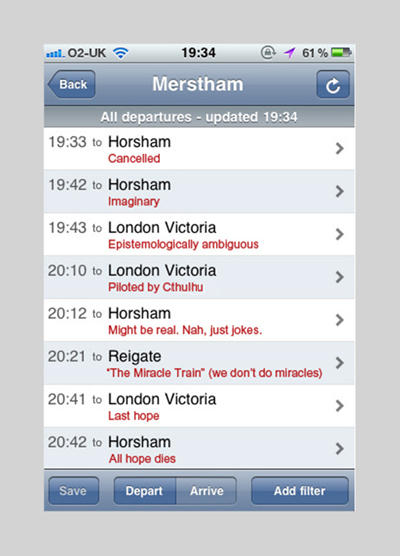

The train operators – possibly out of a sense of decency and fairness, but more realistically under the thumb of the regulators – now operate money-back schemes for many of their services. If the train runs significantly late, or is cancelled, you can claim from them. My operator, like some others, calls it “Delay Repay”.

The burden is on the unfortunate traveller to work out what went wrong, and to make the claim. Sometimes this is easy (I’ve known train operators bring claim forms through the carriage, but that was pre-web days) but often it’s not. You are too busy trying to rescue your day to log the details of just how long you were delayed. Or things have got so chaotic that all concept of which actual train got cancelled/delayed is lost in a mire of misinformation.

If you’re not a season ticket holder then your claim is further complicated by having to dig out the precise fare you paid, which means finding the ticket that you chewed up in disgust after sitting outside New Cross Gate for 90 minutes.

So it’s very likely that Delay Repay is massively underclaimed in practice.

And, as the theory so rightly predicts, if there’s data, and there’s untapped value to be squeezed from it, there’s a business opportunity.

Some clever folk have built this Delay Repay Sniper (DRS) service to do just this.

They get a feed of data from Network Rail every day. For a very modest monthly subscription they will then crunch it around to make sense of it (in its raw format it’s not easy to read or analyse) and email you every day to tell you which (if any) of your preferred routes had problems. They also offer more elaborate features such as the ability to make automatic claims for delays on a particular route.

This, and indeed much of the DRS service overall, has a particular appeal for the season ticket holder. Their routes, fare and train times are usually quite predictable.

But why wouldn’t the train operators just publish this performance information openly on their own sites?

Hmm. Let me think about that.

You see the problem? Although everyone involved is very clear that making a claim when you aren’t entitled to it is fraud, and this is very bad (which it is) – there are certain difficulties in practice.

You don’t even have to travel on a train to make the claim – because of course you can’t, by definition, if it’s been cancelled. You can’t even rely on a swipe at a ticket barrier to show intent to travel – who would leave the concourse (or even, in the case of my journey from home, my house) to do that if the signs (and apps) are all saying “cancelled”?

The Delay Repay claim form I use also asks me to say how long I was delayed. What does that mean? How much additional time it took me to reroute, bus, cycle and hike to my destination, end-to-end? Or how much the train I’d planned to get was delayed?

They don’t specify – because it’s not in their interests to do so – nor is it a clear concept. So they let the user choose how long they were delayed, in bands from 30 minutes to 120+. (My view on this is simple: if the train is cancelled, it’s always entered as a 120+, even if the next service comes along in 25 minutes. If they run it with a delay, then I use that time. My appointments, decisions and connections depend on trains running. They cancel; their problem. If I’m reading this wrongly, I welcome any official guidance…)

So DRS creates the potential for widespread fraud – enabled by the release of data. Perhaps “creates” is too strong – the potential already exists – but it certainly makes it a lot easier. To put it another way, DRS do show people where the potholes are so they can drive into them, exactly as my gloomy local government contact predicted all those years ago.

The train companies are fighting back, of course. Since DRS set up shop, the Delay Repay form has added a Captcha (to hamper automated applications) – an additional tick required to confirm the journeys were actually real (or really intended, I guess) – and stronger warnings against fraudulent claims. They’ve also changed the way that log-in works so that I have to manually fill out all the fields pretty much every time I use the form – passive aggression in interaction design if ever I saw it.

I’ve also had claims reduced or knocked back for being not as delayed as I’d thought – it’s not really worth fighting over each of these, because of some of the ambiguities of terminology mentioned above.

They hint that they’re using analytics to find the patterns of the “world’s unluckiest commuter” whose train is always the precise one that’s been cancelled. Or even, in extremis, would they scan social media to find those holiday snaps from Ibiza when the claim is for a dreary March morning in Ifield? Ok, maybe that’s going too far, for now…

Warnings based on statistics are one thing, mind you – prosecutions or withdrawal of tickets are an entirely different matter. I’m looking with interest for the first court case; because I am certain it will come. It’s massively in their interests to find someone to hit, and hit them hard. [See update below, 28 April 2017]

There is no doubt that an arms race is underway. DRS emailed me with the latest technical changes at their end to get automated claims working again, for example, in response to the introduction of the Captcha verification.

If one pays for a service, one wants to at least recover the cost of subscribing, so there will always be temptation. And in the mind of the commuter, perhaps the moral issues are more complex. All those missed claims because the information wasn’t at hand? Surely it’s fair to make up a few of them here and there? That time when they dumped me off the train at Purley at midnight, then fast-ran it through my bloody station…

You can see how the arguments stack up. I feel a certain level of sympathy for the operators, of course – they have to pay out for delays, and they will only ever be able to manage, not eliminate, fraud.

There’s also a strong whiff of inequality about all of this – the information-rich get a better deal than those who aren’t aware of what and how to claim. I can see ways to improve that, but they’d all require the operators to do – and spend – more. Probably unlikely to happen, in that case.

So – no great conclusion other than to marvel at what complex moral and societal issues surround even something as simple as historical train information.

I can certainly see that DRS add enough value with their unpacking of the stream of raw data, and their email alerts and other services, to give them a business model.

At least until a competitor arrives to undercut them. Market forces tend to keep running, even if the trains don’t.

You’ll be pleased to know that I wrote this over a succession of heavily delayed train journeys. And yes, I am a DRS subscriber.

*The insertions in this popular phrase are “Yellow” and “Rubbery” in this, my favourite variant of it.

Update: 31 March 2016

As ever, starting discussions in an area like this quickly leads to new and better information. What I learned, thanks to Chris Northwood and others, is that DRS don’t get a pre-packaged delivery of this data every day from the train operators. It wouldn’t make sense, really, if you think about it – why would a train operator do that?

What they’re doing (perhaps they’d like to add a comment?) is drawing on the Network Rail feeds, which are, more or less, made available as open data. I duly signed up just now and had a look. Gosh, it’s raw. Really raw. Hefty chunks of JSON, yours to do with as you wish.

It nicely demonstrates an open data business case. DRS are adding tremendous value by taking it in each day, crunching it into something usable, and sending people the precise parts that are most useful to them. Well done them for spotting the opportunity (whatever the motivations of its users may be) and creating a business on top of the data.

The argument remains open as to whether train operators should do that legwork for their customers – if they really wanted to help them – but it would simply add a cost that they’d have to cover somewhere else. Value is value – whoever adds it. There are no free rides here.

Update: 28 April 2017

And here’s that court case I predicted…