Jan 31, 2012 2

Fare dealing

Remind me again: what’s the purpose of opening up all this public data?

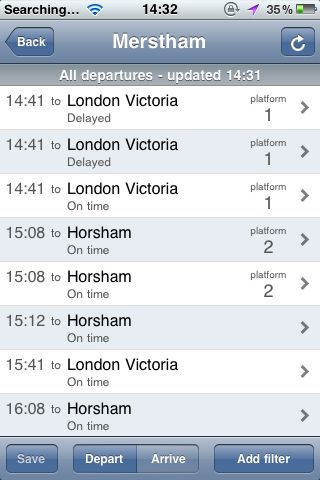

Ah yes, that’s it. To create value. And you can’t get a much stronger example of real value in the real world than showing people how to save money when buying train tickets.

Fare pricing is a fairly hit-and-miss business, as you’ve probably noticed. We don’t have a straight relationship between distance and price. Far from it.

The many permutations of route, operator and ticket type throw up some strange results. We hear of first class tickets being cheaper than standard, returns cheaper than singles, and you can definitely get a lower overall price by buying your journey in parts, provided that the train stops at the place where the tickets join.

The rules here are a bit weird: although station staff have an obligation to quote the cheapest overall price for a particular route, they aren’t allowed to advertise “split-fare” deals, even where they know they exist. Huh?

Why this distinctly paternalistic approach? Well, say the operators: if a connection runs late, your second ticket might not be eligible, and there might be little details of the terms and conditions of component tickets that trip you up, and, and, and…well, it’s all just too complicated for you. Better you get a coherent through-price (and we pocket the higher fare, hem hem).

There’s no denying it is complicated. Precisely how to find the “split-fare” deal you need is a tiresome, labour-intensive process of examining every route, terms and price combination, and stitching together some sense out of it all. And, indeed, in taking on a bit of risk if some of those connections don’t run to time.

You might be lucky, and have an assistant who will hack through fares tables and separate websites to do you that for you. But you’d be really be wasting their time (and your money).

Because that sort of task is exactly what technology is good at.

Taking vast arrays of semi-structured data and finding coherent answers. Quickly. And if there’s some risk involved, making that clear. We’re grown-ups. We can cope.

There’s no doubt at all that the raw materials–the fares for individual journey segments–are public information. Nobody would ever want, or try, to hide a fare for a specific route.

So when my esteemed colleague Jonathan Raper–doyen of opening up travel-related information and making it useful–in his work at Placr and elsewhere, put his mind to the question of how new services could crunch up the underlying data to drive out better deals for passengers, I don’t doubt that some operators started to get very nervous indeed.

Jonathan got wind–after the November 2011 meeting of the Transport Sector Transparency Board–that a most intriguing piece of advice had been given by the Association of Train Operating Companies (ATOC) to the Department for Transport on the “impact of fare-splitting on rail ticket revenues”.

Well, you’d sort of expect an association which represents the interests of train operators to have a view on something that might be highly disruptive to their business models, wouldn’t you?

So what was that advice? He put in a Freedom of Information request to find out.

And has just had it refused, on grounds of commercial confidentiality.

This is pretty shocking–and will certainly be challenged, with good reason.

Perhaps more than most, I have some sympathy with issues of commercial reality in relation to operational data. We set up forms of “competition” between providers for contracts, and in order to make that real, it’s inevitable that some details–perhaps relating to detailed breakdowns of internal costs, or technical logistics data–might make a difference to subsequent market interest (and pricing strategy) were they all to be laid out on the table. I really do understand that.

But a fare is a fare. It’s a very public fact. It’s not hidden in any way. So what could ATOC have said to DfT that is so sensitive?

The excuse given by DfT that this advice itself is the sort of commercial detail that would prejudice future openness is, frankly, nonsense.

I look forward to the unmasking of this advice. And in due course to the freeing-up of detailed fares data.

And then to people like Jonathan and Money Saving Expert creating smart new business models that allow us to use information like it’s supposed to be used: to empower service users, to increase choice, and to deliver real, pound-notes value into the hands of real people.

That’s why we’re doing all this open data stuff, remember?