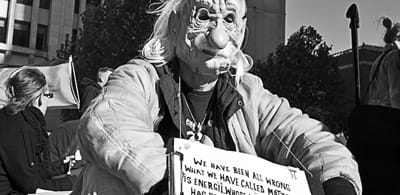

Bad beyond compare

A policy so incredibly inhuman that it stops you in your tracks. How could this ever have been dreamed up? Who thought this would ever be acceptable? How on earth did a blank-faced politician manage to express it in cold,…

The People Photographer

The People Photographer

A policy so incredibly inhuman that it stops you in your tracks. How could this ever have been dreamed up? Who thought this would ever be acceptable? How on earth did a blank-faced politician manage to express it in cold,…

I’ve just done a bad thing. As a photographer, I’ve got a great deal of respect for the work of others. When copyright is held by someone else, and I don’t have a licence to take it or tinker with…

An interesting piece appeared on the Guardian data blog on Friday. It describes a wealth of new data being released relating to court and conviction information. The database shows sentencing in 322 magistrates and crown courts in England and Wales.…

It happened a few months back. Facebook (that hideous, grunt-cheering, dumb-arse cesspit of a privacy clusterfuck–but let me try and remain objective) started to put some rather strange suggestions for new “friends” up on the top right. People who weren’t…

Picture this. You’re walking down the street one day and a strange figure blocks your path. They’re clad head-to-foot in a black sheet. They’ve got some strange sort of voice scrambler strapped to their mouth beneath, and you hear this…

No technology contracts bigger than £100m. Bye-bye proprietary software monopolies–hello Open alternatives. An avalanche of government data to generate new business opportunities and pump billions into the economy. Fast broadband for (almost) all. Agility, everywhere–no more risk-averse, unchangeable systems–instead, a…

This isn’t really a blogpost. Just a tiny anecdote about the power of the information at our fingertips, and how, in less than a minute, it can delight and surprise. I do try and look at photography other than my…

The factual bits: A charity announces its forthcoming annual balloon release. A campaigner highlights the environmental consequences of balloon releases, and posts his objections–backed up with references–on the Facebook page of the charity. The references look to have a sound…

If you follow me on Twitter you might have spotted a recent exchange of views over the last few days with Vodafone. They do a fair job, it has to be said, of engaging in that channel. I’m not sure…

We’re all entitled to our own reaction. To catastrophe, to unexpected joy, to death. When people get very involved in the death of someone they didn’t know, I am slightly puzzled. Of course it is their right. But all behaviours…

In which I look more closely at one particular, well-known data set: what makes it what it is, and what we might draw from the way it’s managed to help us with some other challenging questions about privacy and transparency.…

Nobody tells me how to think. That’s important. A core value. Influence me, by all means. Educate me as much as you can. Push me to see something from a different angle. Lend me your shoes and let me walk…